This blog is titled “Prison Culture” and yet I write relatively little about the actual culture inside prisons. This is primarily because I have never been incarcerated so I only have an observer’s vantage point from which to address the issue. This is necessarily limiting.

On Monday evening, I spent over two hours listening to Bennie Lee break down the concept of prison culture in the late 1960s into the mid-1970s. I so wish that I had brought a tape recorder with me because his stories were incredibly rich and his knowledge very deep.

by Andalushia Knoll

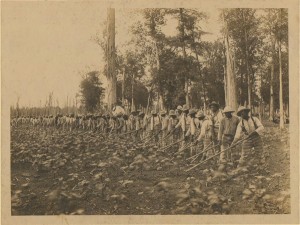

As Bennie discussed the prison culture of the 60s and 70s which helped to shape his political and social consciousness, my mind began to race about how to present this information in the upcoming exhibition about the history of black incarceration in the U.S. that I am co-curating. What was clear to me in listening to Bennie is that some black prisoners of the mid-60s through the mid-70s were unique. They were centrally engaged in debates and discussions about incarceration, racism, civil rights, & colonialism that were happening both inside and outside the walls of prisons across the U.S during that era.

Bennie spoke about the overt and covert educational groups that prisoners at Stateville and other Illinois prisons organized. As a prisoner, he was steeped in reading books by Khalil Gibran, Don Lee, Malcolm X, Franz Fanon, and more. He recited several oaths of the Conservative Vice Lords, one of which was actually based on Gibran’s “the Garden of the Prophet.” It was mesmerizing and thought-provoking.

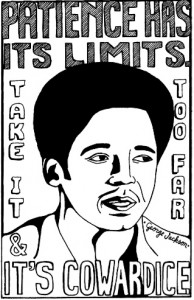

A few months ago, I came across the list of books that were found inside George Jackson’s cell when he was killed at San Quentin in 1971. I was stunned by the sheer number of books but also by the fact that I had only read maybe 30 of them.

by Katy Groves

Lee Bernstein (2007), who I have quoted several times on this blog, has written about the importance that the ideas of Malcolm X, Angela Davis, and George Jackson had on the consciousness and the writings of a generation of incarcerated people in the 1970s. In writing particularly about Jackson’s influence, Bernstein (2007) suggests that:

“To prisoners, Jackson was as much a teacher of radical political philosophy and spokesperson for a crisis behind bars as symbol of oppression. His education behind bars and uncompromising politics would come to serve as a model for prisoners (p.312).”

Read more »